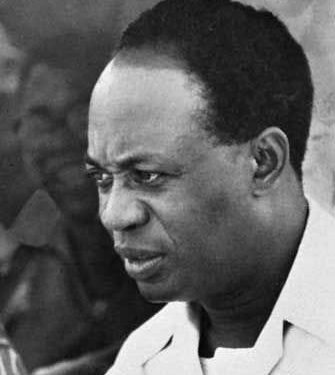

Kwame Nkrumah, the first President of Ghana and a prominent advocate of Pan-Africanism, envisioned a united and self-reliant Africa. His dream was of a continent free from colonial influence, economically independent, and politically integrated. Today, the question arises: Would Nkrumah be satisfied with the current state of the Pan-African agenda?

Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism was rooted in the struggle for independence and the belief that unity was essential for Africa’s progress. He spearheaded initiatives like the formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, aiming to foster cooperation and prevent external interference. Nkrumah’s ideology emphasized economic self-sufficiency, social justice, and the eradication of neocolonialism.

One of Nkrumah’s core goals was the economic integration of Africa to reduce dependence on foreign aid and trade. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), launched in 2021, aligns with his vision by promoting intra-African trade and economic cooperation. This initiative represents a significant step towards economic integration, potentially boosting the continent’s GDP by $450 billion by 2035.

However, challenges remain. African economies are still heavily reliant on exporting raw materials and importing finished goods, a structure reminiscent of the colonial era. Moreover, infrastructure deficits, political instability, and weak institutions hinder full economic integration. Nkrumah would likely acknowledge AfCFTA as progress but urge for more robust efforts to achieve true economic independence.

Nkrumah advocated for a United States of Africa, a political union that would present a unified front on the global stage. Today, the African Union (AU) continues to promote political cooperation, conflict resolution, and regional integration. Initiatives like the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) aim to improve governance and accountability.

Despite these efforts, political fragmentation and internal conflicts persist. Ethnic tensions, autocratic regimes, and electoral disputes undermine unity. Nkrumah would probably be critical of the AU’s limited effectiveness in enforcing democratic principles and resolving conflicts. He would call for stronger political will and leadership to achieve genuine unity.

Social Justice and Human Development

Nkrumah’s vision extended to social justice, emphasizing education, healthcare, and equality. Significant progress has been made in these areas. Primary school enrollment rates have increased, life expectancy has risen, and poverty rates have declined.

Yet, disparities in wealth, education, and healthcare access remain stark. Rapid population growth, urbanization, and unemployment present ongoing challenges. Nkrumah would likely recognize these advancements but stress the need for more inclusive development policies to ensure that the benefits of growth reach all Africans.

Nkrumah championed a cultural renaissance, encouraging Africans to reclaim their heritage and identity. Contemporary movements in art, music, and literature reflect a vibrant cultural resurgence. Initiatives like the African Renaissance Monument in Senegal and the return of African artifacts from Western museums symbolize a renewed pride in African heritage.

Nevertheless, cultural imperialism through globalization and Western media influence continues to shape perceptions and values. Nkrumah would advocate for stronger efforts to preserve and promote African culture, urging educational reforms and media representation that reflect Africa’s rich diversity.

Global Influence and Partnerships

Nkrumah envisaged Africa as an influential player on the global stage. Today, Africa’s voice in international forums like the United Nations and the World Trade Organization has grown. Strategic partnerships with emerging powers like China and India offer new opportunities for development.

However, these partnerships often come with challenges, including debt dependency and unequal terms of trade. Nkrumah would likely caution against replicating neocolonial patterns and emphasize negotiating equitable and mutually beneficial agreements.

In evaluating whether Nkrumah would be happy with today’s Pan-African agenda, it is clear that significant strides have been made towards his vision. Economic initiatives like AfCFTA, political cooperation through the AU, and cultural resurgence all reflect elements of his dream. However, persistent economic dependency, political fragmentation, social inequalities, and cultural challenges indicate that much work remains.

Nkrumah would probably commend the progress but insist on a more vigorous pursuit of Pan-African ideals. He would call for enhanced economic strategies, stronger political unity, deeper social justice, and a robust defense of African identity. His enduring legacy reminds us that the path to a truly united and self-reliant Africa is ongoing, requiring relentless dedication and visionary leadership.