Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal’s newly elected

Following his inauguration, Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal’s newly elected “left Pan-Africanist” president, wasted no time in declaring a significant governmental initiative. He announced a comprehensive audit of Senegal’s oil, gas, and mining industries. Faye emphasized, “The utilization of our natural riches, constitutionally owned by the populace, will be a focal point of my administration.” Furthermore, he asserted that current agreements with energy giants such as BP would be subject to renegotiation should the need arise.

Faye’s triumph in the campaign adds to a growing pattern in West Africa

Faye’s triumph in the campaign adds to a growing pattern in West Africa, where numerous new administrations are emerging with a strong emphasis on political and economic autonomy. These governments are rejecting the neo-colonial influence that has prevailed over the continent since the middle of the 20th century. In a similar vein, Niger, among these nations, has taken decisive action by demanding the withdrawal of all U.S. military personnel from its territory.

developments have sparked significant concern

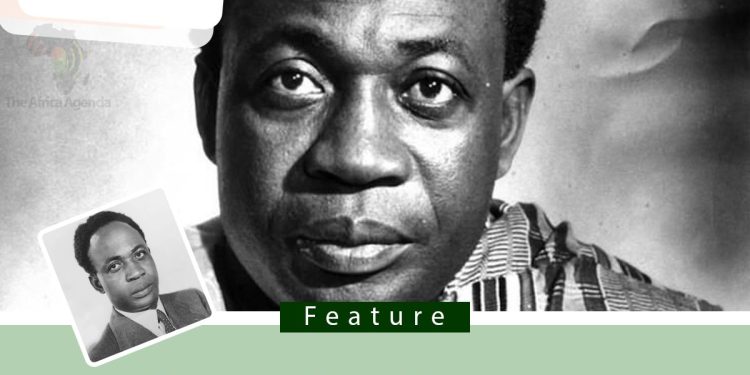

These developments have sparked significant concern within the realm of U.S. imperialism. Government and military figures from the United States have publicly deliberated on Africa’s strategic significance, pondering methods to uphold maximum control over the continent. Reflecting on historical parallels, the case of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s inaugural president and prime minister, offers insights into potential responses by U.S. imperialism to the evolving landscape in West Africa.

Kwame Nkrumah’s pivotal role in shaping the course of Pan-Africanism

Kwame Nkrumah’s pivotal role in shaping the course of Pan-Africanism and Ghana’s independence is indelible. Born out of British colonization in 1874, Ghana, then known as the “Gold Coast Colony,” witnessed a fervent rise in its national liberation movement by the late 1940s. Nkrumah emerged as a prominent figure within two of the colony’s foremost political parties: initially the United Gold Coast Convention and later the Convention People’s Party (CPP). Despite Britain’s attempts to tightly control the impending independence process by imprisoning Nkrumah and other CPP leaders, the party triumphed in the 1950 elections, dealing a significant blow to British colonialism.

In 1957, Ghana achieved independence, marking a watershed moment not only for the nation but also for Africa as a whole. Nkrumah ascended to the positions of prime minister and later president, wielding his influence to champion Pan-Africanism and socialism. His visionary leadership extended beyond Ghana’s borders as he spearheaded initiatives to bolster Africa’s political and economic sovereignty in an era when much of the continent remained under colonial rule.

In 1958, Nkrumah convened a historic gathering of leaders from eight independent African states, laying the groundwork for the inaugural All-African Peoples’ Conference held in Accra that same year. This landmark event brought together 300 delegates with a singular objective: to forge unity in the struggle against colonialism and imperialism across the continent. Nkrumah’s unwavering commitment to Pan-African solidarity and liberation resonated deeply, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to inspire generations.

In 1963, Kwame Nkrumah’s pivotal influence extended to the establishment of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), a monumental milestone in the quest for African unity and liberation. Initially comprising 32 member states, the OAU was founded with five fundamental objectives:

1. Promoting the unity and solidarity of African states, fostering a sense of common purpose and collective action among nations on the continent.

2. Coordinating and enhancing cooperation among member states to advance the well-being and prosperity of Africa’s peoples, striving for tangible improvements in their lives.

3. Defending the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence of African nations, safeguarding them against external threats and interventions.

4. Eradicating all forms of colonialism from Africa, reaffirming the continent’s commitment to self-determination and freedom from foreign domination.

5. Promoting international cooperation, while upholding the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, reflecting Africa’s engagement with the global community while asserting its values and aspirations.

Nkrumah’s instrumental role in shaping the OAU underscored his enduring dedication to Pan-Africanism and his vision for a united and liberated Africa. Through the OAU, African nations collectively charted a path towards greater solidarity, self-reliance, and progress, leaving an indelible mark on the continent’s history and future trajectory.

Kwame Nkrumah’s seminal work, “Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism,” stands as a powerful critique of the evolving mechanisms of imperialism in the post-colonial era. In this groundbreaking book, published in 1965, Nkrumah astutely identifies and defines the concept of neo-colonialism, shedding light on the subtle yet pervasive forms of control wielded by imperial powers in the wake of formal decolonization.

Nkrumah argues that while the era of overt colonial rule may be waning, imperialism persists through the insidious guise of neo-colonialism. In this new paradigm, nominally, independent states retain the trappings of sovereignty on the international stage, yet external forces effectively dictate their economic systems and political agendas. This phenomenon, according to Nkrumah, represents a sophisticated strategy by imperial powers to maintain dominance over formerly colonized territories, utilizing financial advantage and economic dependency as tools of control.

Indeed, Nkrumah’s analysis rings particularly poignant in the context of his own country, Ghana, where the promise of independence was marred by the encroachment of neo-colonial influences. Despite achieving formal sovereignty, Ghana found itself ensnared in a web of economic exploitation and political manipulation, highlighting the enduring grip of imperialism in the post-colonial era.

Nkrumah’s elucidation of neo-colonialism remains a vital lens through which to understand the complexities of global power dynamics and the ongoing struggles for genuine independence and self-determination in the Global South. His insights continue to resonate, inspiring efforts to dismantle systems of oppression and chart a path towards true emancipation.

Nkrumah’s unwavering commitment to socialism and Pan-Africanism, coupled with his willingness to collaborate with the Soviet Union and China, marked him as a perceived threat in the eyes of the U.S. government. As he sought to advance Ghana’s socialist experiment and foster anti-imperialist consciousness across Africa and the globe, Nkrumah increasingly drew the ire of U.S. policymakers.

In December 1957, a mere nine months after Nkrumah assumed leadership of an independent Ghana; the CIA circulated a now declassified report entitled “The Outlook for Ghana” to key governmental bodies including the White House and the National Security Council. This report underscored concerns that Nkrumah’s ambitious agenda, aimed at rapidly modernizing Ghana’s economy and promoting Pan-African solidarity, would face significant challenges due to the country’s limited financial resources. As a result, the report laid the groundwork for U.S. policy towards Nkrumah and Ghana, shaping subsequent actions taken by the American government.

The implications of this report set the stage for covert U.S. intervention in Ghana’s internal affairs, ultimately culminating in a CIA-backed coup aimed at ousting Nkrumah from power. This intervention not only spelled the end of Ghana’s socialist experiment but also dealt a severe blow to the broader Pan-Africanist movement and anti-imperialist struggles in Africa.

The declassified report served as a blueprint for U.S. efforts to undermine Nkrumah’s leadership and dismantle his vision for Ghana and Africa. It underscores the lengths to which imperial powers would go to thwart movements for self-determination and sovereignty, revealing the enduring legacy of colonialism and imperialism in shaping global geopolitics.

Largely economic interests will probably shape attitudes and policies toward the U.S. A growing number of Ghanaians have visited the US, where they have been particularly impressed by technical achievements, but repelled by the racial discrimination, which they encountered. Both on the latter count and because of the extremes in which anticolonialism is expressed, Ghana does not find moderate U.S. policies very appealing. Ghana nevertheless is favorably disposed toward the US.. at present, especially since it is regarded as the logical source of the foreign capital and technical assistance essential for the Volta Project, and Ghana is likely to make large requests for aid in the near future…

We believe that Ghana’s desire to avoid close alignment with any great power and to act independently in African affairs will limit both Soviet and Western influence in at least the short run. However, the practice of the [socialist] Block taking positions on ‘colonial’ and racial matters similar to those of the former colonies will often result in Ghana’s lining up with the Bloc on certain issues before the UN. These relationships are likely to develop regardless of any countering Western actions.

The Volta Project stood as a cornerstone of Kwame Nkrumah’s ambitious vision to modernize Ghana’s economy, leveraging the potential of hydroelectric power to fuel industrial expansion, particularly in the production of aluminum, an abundant natural resource in Ghana. However, the project also became a focal point of geopolitical maneuvering, with the U.S. government strategically funding it to forestall Ghana’s alignment with the socialist bloc and maintain a degree of influence over the country.

Despite U.S. support for the Volta Project, Nkrumah’s steadfast opposition to colonialism and imperialism continued to strain relations with the United States. As tensions mounted, the U.S. government initiated covert efforts to undermine Nkrumah’s leadership and orchestrate his downfall. In 1964, Mahoney Trimble, the Director of the Office of West African Affairs at the U.S. State Department, outlined an “action program” designed to exert pressure on Nkrumah’s administration. This program aimed to exploit vulnerabilities within Ghana, leveraging economic advantage, psychological warfare tactics, and diplomatic maneuvers to sow dissent and ultimately engineer Nkrumah’s removal from power.

Key components of the action program included withholding or delaying payments for the Volta Project, employing psychological warfare tactics to erode support for Nkrumah within Ghana, and mobilizing other African leaders against him. This concerted effort reflected the lengths to which the U.S. government was willing to go to safeguard its interests and counter perceived threats to its influence in Africa.

The Volta Project, initially envisioned as a catalyst for Ghana’s economic development, thus became embroiled in broader geopolitical rivalries, underscoring the complexities of international relations in the post-colonial era and the challenges faced by nations striving for genuine independence and sovereignty.

The United States actively cultivated ties with factions within Ghana that eventually orchestrated the successful coup against Kwame Nkrumah in February 1966. A revealing 1965 internal memorandum from Robert Komer of the National Security Council underscored U.S. involvement, indicating that certain military and police figures within Ghana had long been planning a pro-Western coup, with the country’s deteriorating economic conditions serving as a catalyst.

The memorandum suggested that the United States, along with other Western countries such as Britain and France, played a role in setting the stage for the coup by withholding economic aid despite Nkrumah’s appeals. Furthermore, compelling evidence points to direct CIA involvement in the coup. In 1978, credible sources within the intelligence community disclosed to the New York Times that the CIA had advised and supported the coup plotters. John Stockwell, a former CIA operative, in his book “In Search of Enemies”, corroborates this claim.

Following the coup, the U.S. government swiftly extended financial and diplomatic support to the new regime to ensure that Nkrumah and his party, the CPP, could not regain power. This included the expedited delivery of 500 tons of milk to alleviate the hardships exacerbated by the economic turmoil that the United States had contributed to only months earlier.

These revelations underscore the extent to which the United States actively intervened in Ghana’s internal affairs to safeguard its geopolitical interests, undermining the principles of sovereignty and self-determination. The coup not only marked the end of Nkrumah’s socialist experiment but also dealt a severe blow to the broader Pan-Africanist movement and aspirations for genuine independence in Africa.

The struggle against neo-colonialism remains a pressing concern, with echoes of Kwame Nkrumah’s vision reverberating in the aspirations of contemporary African leaders who reject external domination. As observers in Africa, it is imperative that we delve into the history of U.S. intervention in Ghana and across Africa to better comprehend and confront the challenges that lie ahead.

Nkrumah’s experience underscores the hybrid nature of imperialism’s tactics, which encompass economic coercion, information warfare, political manipulation, and, if necessary, military intervention to thwart the emergence of sovereign African nations. However, amidst shifting global dynamics and a waning influence of U.S. imperialism, there is a growing tide of anti-imperialist consciousness within the United States. As more countries assert their independence and refuse to bow to colonial domination, the traditional strategies of neo-colonialism are poised to encounter formidable resistance.

Indeed, the struggle against neo-colonialism is far from over, but the resilience of African nations and the rising anti-imperialist sentiment worldwide offer hope for a future free from external interference and exploitation. By understanding and confronting the historical legacies of imperialism, we can stand in solidarity with those fighting for genuine sovereignty and self-determination, both within Africa and beyond.