The Partition of Africa, initiated at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, laid the groundwork for the continent’s current borders, a legacy that continues to shape African geopolitics today. Convened by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the conference aimed to prevent conflict among European powers over colonial claims in Africa, establishing a framework for the division of the continent without any African representation.

The Participants and Their Motives

All major European powers—Germany, France, Great Britain, Belgium, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Spain—attended the conference, driven by imperial ambitions and a desire for economic gain. Notably absent were any African leaders, underscoring the disregard for indigenous voices in decisions that would irrevocably alter their lands and lives. The conference emphasized the need for European powers to bring “civilization,” often framed as Christianity and trade, to the territories they claimed. However, the process for establishing territorial claims was superficial, often involving mere military outposts and vague agreements with local rulers, who frequently lacked the knowledge or literacy to comprehend the contracts they signed.

The Scramble for Resources

The conference focused primarily on unclaimed interior regions of Africa, as coastal territories had already been divided among European nations. The lack of prior exploration meant that much of Africa remained a mystery to Europeans, yet the allure of its abundant natural resources—rubber, gold, diamonds, and palm oil—soon led to increased incursions into the continent’s interior. By 1900, the economic motivations of European powers shifted the focus from mere occupation to the extraction of resources, fundamentally altering the continent’s landscape and social structures.

One of the most infamous outcomes of the Berlin Conference was the personal claim to the Congo Free State by King Leopold II of Belgium. While the area was designated for free trade among European nations, Leopold’s regime became synonymous with exploitation and brutality, as local populations were forced into labor under horrific conditions. This dark chapter of colonial history eventually prompted international outrage, leading to the transfer of the Congo to direct Belgian government control in 1908.

The Enduring Impact of Arbitrary Borders

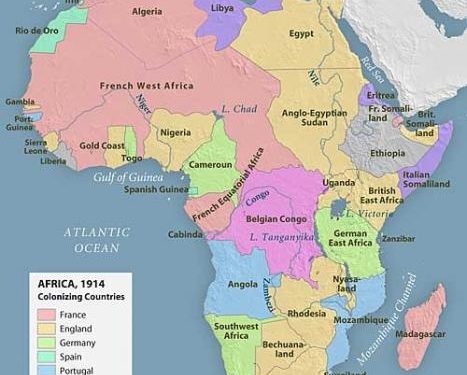

By 1914, nearly 90% of Africa was under European control, with only Liberia and Ethiopia retaining their independence. The arbitrary borders established during the Berlin Conference often ignored ethnic, cultural, and historical realities, leading to lasting conflicts that persist to this day. The legacy of these borders is evident in the ongoing struggles for identity and unity within African nations, as well as in conflicts that arise from the grouping of diverse ethnic groups into single political entities.

Following decades of resistance, the wave of decolonization began in earnest in the mid-20th century, starting with Ghana’s independence in 1957. By the turn of the millennium, virtually all African nations had gained independence, yet many grappled with the consequences of colonial rule and the arbitrary borders that had been imposed upon them.

The Berlin Conference stands as a stark reminder of the complexities of Africa’s colonial past and the lasting implications of its partition. As African nations continue to navigate the challenges posed by these historical injustices, the pursuit of unity, identity, and self-determination remains vital. Understanding this history is essential for fostering dialogue around reconciliation and development in the contemporary African context.